The People’s Kitchen

Imagining an Eco-Socialist Future through Dumpster Diving & Food Sharing

The People’s Kitchen Palestina Encampment 2024 (Credit: Ariane Evertz)

It's my third week in the Swedish university city of Lund after moving here for my studies, when one of my new classmates invites me to dinner on Thursday evening at a place called the Folkets Kök (People’s Kitchen) organized by the Ecosocialist Collective.

“It’s a free dinner they host every Thursday, run by volunteers and anyone is welcome to join.”

“It’s free?” I ask. I must have misunderstood, surely there must be something like a membership fee attached for a meal to be free of charge.

“Well, it’s possible to donate anything you can spare, but most of the food is dumpster-dived, the donated money is then used to buy the remainder of groceries to create the meal.” She stated it so matter-of-factly, but I needed a second to wrap my head around the concept of a free dinner prepared from thrown-away food. Living under the capitalist system — a system in which every basic necessity is commodified — it seems outrageous to imagine an actually free meal with no strings attached. The three new concepts struck me: free communal dinners, dumpster diving, and ecosocialism.

The Dumpster Divers & Ecosocialism

I soon discovered that the practice of dumpster diving is quite normal among the students of Lund – from my roommates to the people in my classes: scavenging through supermarket bins after 10pm looking for discarded, edible food is a part of their weekly routine. And they are not alone, dumpster diving is taking place in many countries in the Global North: from Finland, Germany, Denmark and Austria to Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

I learned that eco-socialism aims to weave together humanist and ecological values as a way to move beyond capitalism. By combining concerns of social justice and the environment, eco-socialist movements intend to “subordinate exchange-value to use-value, by organizing production as a function of social needs and the requirements of environmental protection”. In other words: constructing production around necessity rather than profit, while respecting and replenishing the natural environment. In addition to Marxism and environmentalism, the eco-socialist movement has been informed, inspired, and influenced by (eco)feminism, Indigenous knowledge, anarchism, and movements for food and land sovereignty, to name a few.

With this in mind, I felt that the People’s Kitchen encapsulated something wildly interesting. I asked myself: How does this initiative embody eco-socialist values through the use of wasted resources and sharing of food, and to what extent does this possibly form a gentle act of resistance against the capitalist system? By exploring capitalism through the lens of the industrial food system and its consequent environmental and social implications, we can analyze dumpster diving as an intriguing site for anti-capitalist critique. The People’s Kitchen operation dives into the opportunities to rebuild systems centered around community-building and values of reciprocity.

The People’s Kitchen Palestina Encampment 2024 (Credit: Ariane Evertz)

Food production under capitalism: ecological & social implications of food waste

One of the intriguing aspects of capitalism is the way in which its principles have not only dominated the realm of economics but have indeed also spread to other areas – constituting not just an economic but a whole social system. Some of capitalism’s fundamental characteristics include – but are not limited to – endless need for capital accumulation (i.e., economic growth), consumption culture, maximization of profit and exploitation of labor-power and natural resources. These principles also dominate the food system: “The food supply chains are significantly determined by markets, which shape how and where food is produced, processed, sold and consumed”. This has ultimately led to the commodification of food: it is a product to be sold on the market to generate surplus-value, rather than a basic human need that should be equally accessible to all people. This refers back to my confusion on the idea of being able to enjoy a free meal every week and illustrates the deeply ingrained, supposed naturality of this notion that everything should be paid for. Furthermore, by organizing the food supply chain around money and the maximization of profit, social and environmental impacts are not included.

As Steven Stoll explains, “capitalism obscures every connection to the origins of things, it hides the political social relations, and environmental change inherent in how things turn into commodities”. The exclusion of these hidden costs allows for the input of cheap resources – including raw materials as well as labour-power – which in turn allows for profit maximization. In other words, the exploitation of human labour and nature is fundamental to the creation of surplus-value.

The ecological and social consequences of this externalization of costs materialize in different ways. As for the environment, the industrial food system bears a heavy burden on ecosystems as it uses large quantities of resources such as water and fossil fuels in a way that is ecologically highly unsustainable. Further, the overwhelming use of monocultures on large pieces of land have led to biodiversity loss and soil erosion, and the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides have led to the pollution of water, soil and air. Additionally, food systems are highly carbon-intensive and contribute to over a third of annual greenhouse gas emissions – being a large contributor to anthropogenic climate change as a result. These ecological implications together – just to name a few – perfectly illustrate one of capitalism’s many contradictions: its tendency to degrade the very ecosystems it relies on for subsistence. Or, as Nancy Fraser puts it: “Simultaneously needing and rubbishing nature, capitalism is a cannibal that devours its own vital organs, like a serpent that eats its own tail”.

Another contradiction resulting from the capitalist production of food is the co-existence of an overabundance of food – with generous amounts of food waste as a result – on the one hand, and large parts of the world population suffering from malnutrition and hunger on the other. Food waste is generated among all stages of the food production process, but especially in distribution and consumption: annually about a third of food produced for human consumption is wasted, overwhelmingly in the Global North. In Sweden specifically, 1.3 million tonnes of food are wasted every year. Some of this waste is categorized as unavoidable waste of food products, such as the inedible parts of food like eggshells, bones, or banana peels. However, a large part of wasted food is considered avoidable. Avoidable food waste – in households or the retail sector for example – refers to edible food that could have been prevented from being thrown away if better managed. Avoidable or unnecessary food waste bears a high environmental cost, as it means the direct waste of natural resources used to create those foods.

In addition to its environmental impacts, industrial food production has led to profound social inequalities – one of which is the large-scale problem of malnutrition and hunger. A United Nations report estimated that as many as 828 million people were affected by hunger in 2021. Many believe that starvation is a problem that can be solved by industrial agriculture, when in reality it is an issue borne out of this very system: “As nations realized that farmland could be used to generate gross domestic product, they evicted peasants and turned land over to industrial firms. The food went for export, and the peasants went to slums. Note the contradiction: more food and more hungry people”. It remains difficult to grasp that there is more than enough food to feed the world population, yet almost a billion people suffer from hunger each year. It is safe to say then that the commodification of the food system under capitalism has not only led to environmental destruction but has also resulted in grave inequalities when it comes to food security. One way in which some aim to protest the implications of this system, is through the practice of dumpster diving.

Dumpster Diving: An Anti-Capitalist Critique?

I must admit, I personally had to warm up to the idea of, to put it bluntly: eating food from the trash. Immediately I experienced this stigma around the concept of waste; it felt dirty and unhygienic. However, when learning more about it – through conversations and literature research – it became clear that most of it is about perspective. When you think about it, the food itself does not magically become dirty or less edible when thrown away. It really comes down to a change in location of the food: from the store to a dumpster. When you consider then that most food in supermarkets is thrown out for aesthetic reasons, due to policies around expiration, or as a result of overstocking due to consumer preferences – you will find plenty of foods in supermarket dumpsters that are still in good condition.

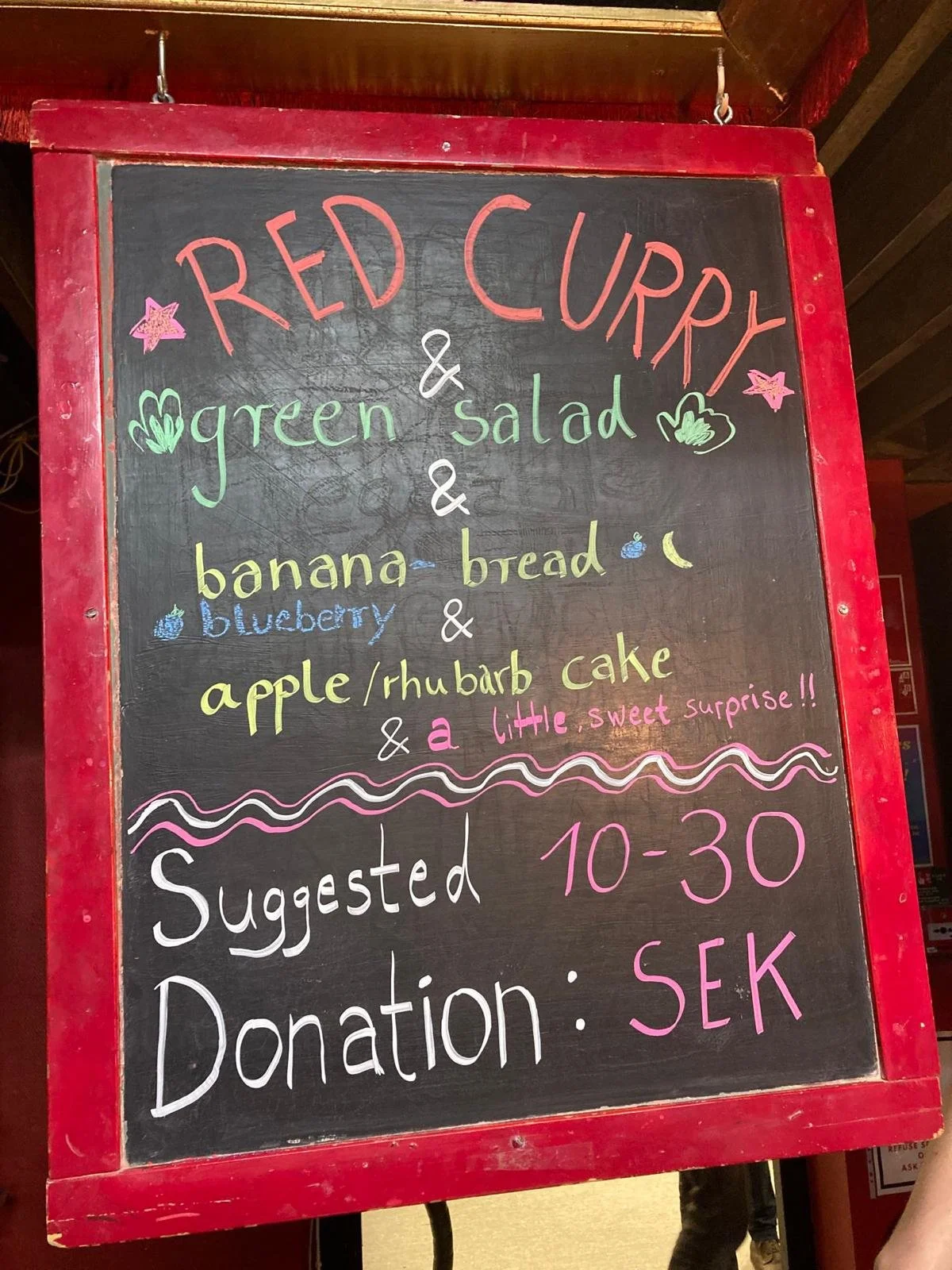

The People’s Kitchen Menu (Credit: Gina de Boer)

There are various motivations for the practice of dumpster diving. Some people do it out of necessity due to food insecurity, although this seems to be a relatively small part. Then there are others who simply do it for the thrill, to obtain a free meal, or as a shared activity with others. Most divers, however, have been found to engage in the activity as an activist practice against consumerism and capitalism. They protest “the dominant taken-for-granted food system under a capitalist mode of production, which is currently causing widespread inequalities and environmental degradation”, as described above. By using dumpster-dived food, divers not only aim to combat food waste; they refrain from participating in the culture of overconsumption. Furthermore, using discarded foods (rather than spending money in a supermarket) is a way of resisting the participation in the accumulation of capital. Through the act of dumpster diving, individuals are able to create some agency as they “carve out a critical space for themselves […] in the midst of an unecological form of life”.

Although dumpster diving can be viewed as an activist practice against capitalism, one cannot help but notice the paradox it brings to the fore. Namely, the act of dumpster diving would not exist without the wastes of capitalism. While dumpster diving is a form of criticism of and resistance against overconsumption and the wastefulness of capitalist modes of production and distribution, it simultaneously depends on these very excesses. Considering this, dumpster diving might not be a way to completely diverge from capitalism. Nevertheless, it is a way – however small – to hold onto one’s integrity and agency within a system that has dominated ever so many, if not all, aspects of life. Dumpster diving allows people the refusal to fully participate in the capitalist system, or at the very least refrain from feeding into it in the realm of the food industry.

Another interesting element of dumpster diving as a form of activism is the setting in which it takes place: where activist practices are typically characterized by and reliant on its visibility in the public domain, dumpster diving predominantly occurs in the quiet hours of the night. Technically, taking things from the trash is not illegal in Sweden (as long as dumpsters are unlocked) however, store owners can ask divers to leave the premises. Therefore, the dumpster divers I have encountered here in Lund engage in the practice after supermarkets close, which in most cases is after 10 in the evening. Once an easily accessible and abundant dumpster has been located, divers – alone or in small groups – scavenge through them after dark, taking however much they can carry home. Fascinatingly, divers appear to adhere to a set of unwritten rules, namely: take only what you need, clean up after yourself, and share products of high quantity or quality with others. Where most forms of resistance usually loudly call for and depend upon attention in the public sphere, dumpster diving happens almost unnoticeably in the shadows. It forms a quiet critique rather than a loud, unmistakeable one.

The People’s Kitchen as a gentle act of resistance: food saving, sharing & reciprocity

Within the People’s Kitchen, however, dumpster diving’s activist roots are brought into the public realm as dumpster-dived food is given a central role in their philosophy – highlighting the problem of food waste and overconsumption. The preparations for the People’s Kitchen start with this very practice, as two volunteers set out to dumpster dive on Tuesday or Wednesday. Depending on the available treasures that have been retrieved on this venture, the coordinating group will brainstorm on what vegan meal they will create with it. On Thursday afternoon, one or two other volunteers will buy the remainder of the necessary groceries to be used that evening. Then there are about three or four more volunteers who bravely signed up to cook for about 40 people between 4 and 7p.m. Lastly, there are about four volunteers who are responsible for serving the food and cleaning up at the end of the evening.

The event is hosted at one of Lund’s student nations, Småland’s, and everyone – students and non-students alike – is welcome to step inside and enjoy dinner together. By about 7 o’clock the room overflows with the smell of a Mexican curry or a freshly baked banana bread. Eager chatter and laughter fill the space as long-time friends, comrades, and strangers exchange smiles and stories of their homelands. In the middle of the evening, one of the coordinators rings the big bell behind the counter to explain the People’s Kitchen to those attending for the first time. For a minute or two the room quiets down as they explain the concept: the meal is free due to the use of dumpster-dived food, but donations are welcome and used for grocery shopping for the remaining ingredients – however, donating is not necessary if you’re not able to. Others are also invited to sign up and volunteer if they have time to spare, and so the word spreads and the community grows.

The scenario I have illustrated above might just sound like a communal student dinner to some, but I feel there is more weight to it. Particularly, one could argue that the People’s Kitchen embodies important eco-socialist principles. As for ecological values, some food waste in Lund is recovered and used each week, which prevents the direct waste of ecological resources spent on those foods. Furthermore, by making the practice of dumpster diving such an integral part of the People’s Kitchen – by forming the meal around dumpster-dived food and then explaining to the attendees every week where the food comes from – the problem of food waste is highlighted and brought into people’s awareness. It holds the potential to make people more conscious of their own consumption habits or even inspire others to engage in dumpster diving themselves. In addition, the meals provided are fully vegan as to have the lowest possible impact on the climate. As for socialist values, the People’s Kitchen’s provision of a (mostly) free meal follows from a philosophy built around fulfilling basic needs (i.e., use-value) rather than making a profit (i.e., exchange-value). Additionally, Folkets Kök forms an eco-socialist manifestation through the sense of community it provides. It is not simply about sharing a meal, it is also about “exploring different ways of being together, and creating a sense of community, whereas the mainstream capitalist economy tends to destroy communities”.

The People’s Kitchen Palestina Encampment 2024 (Credit: Ariane Evertz)

One way in which this community-building is fostered is through the gift economy, as described in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass. Kimmerer discusses the principles of gift exchange as opposed to commodity exchange: “[…] in the gift economy, gifts are not free. The essence of the gift is that it creates a set of relationships. The currency of a gift economy is, at its root, reciprocity”. She talks of an experience she had at a local market in the Andes, where one day all the vendors were handing out their food without accepting money in return. She describes how this influenced her consumption behaviour: “Had all the things in the market merely been a very low price, I probably would have scooped up as much as I could. But when everything became a gift, I felt self-restraint. I didn’t want to take too much, and I began thinking of what small presents I might bring to the vendors tomorrow”. There is a similar experience at the People’s Kitchen, where no one overindulges but takes only what they need to make sure there is enough for everyone. And, as an act of gratitude, attendees are motivated to donate their time and volunteer for one of the next editions. This also links back to one of the unwritten principles handled during dumpster diving: take only what you require and share. As Vaughan found: “The high level of reciprocity and equitable distribution among divers reveals a stark contrast to the values entrenched in our current mainstream food system” dominated by capitalist principles.

In combining food saving through dumpster diving and the sharing of that food within a community, I would argue that the People’s Kitchen constitutes a gentle act of resistance against an ever-present capitalism as it embodies eco-socialist values rather than market-based principles. Perhaps it does not provide us with a full-fledged anti-capitalist alternative, however, it does provide tools to help imagine a system constructed around social and ecological needs rather than profit; where principles of care, comradery and community are central. There is never a shortage of warmth or friendly faces to greet you on a Thursday evening at Småland’s. People are grateful to have a space where they can unwind as students, activists, and humans. A space where a group of comrades have voluntarily poured their care into creating a meal for others to enjoy and be nourished by. As Kimmerer puts it: “I was witness to the conversion of a market economy to a gift economy, from private goods to common wealth. And in that transformation the relationships became as nourishing as the food I was getting”.

I believe that, in order to create more sustainable and equitable ways to organize society, tools are needed to create a new narrative. As Kimmerer stated: “The market economy story has spread like wildfire, with uneven results for human well-being and devastation for the natural world. But it is just a story we have told ourselves and we are free to tell another”. I would argue that initiatives such as the People’s Kitchen could help us envision what a post-capitalist story would look like.

And so, ever since experiencing this brewing potential during my first dinner at Småland’s, I have faithfully joined the People’s Kitchen community every Thursday. Reveling in this space where individuals express their care for the environment and each other so passionately has provided a sense of hope in a world dominated by destructive capitalist principles. And just like I was invited by a kind stranger some two months ago, I have been spreading the word about the People’s Kitchen – aiming to share this hope along the way.

Gina de Boer is a storyteller from The Netherlands. In her work, she strives to build a bridge between academia and storytelling, as she explores topics ranging from climate change to social inequalities, environmental justice and community-building. Having graduated with a double degree in Sustainability and Philosophy at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, she is now finishing her master’s in Human Ecology at Lund University. This has informed her interdisciplinary vantage point, as she’s interested in exploring the interconnectedness of seemingly separate crises - social, environmental, health or other.